![]() A pilgrim’s guide to the Great and Holy Monastery of

Vatopaidi

A pilgrim’s guide to the Great and Holy Monastery of

Vatopaidi

Published by the Great and Holy Monastery of Vatopaidi, Mount Athos 1993

|

The Monastery of Vatopedi. Photo: www.nistea.com

Съдържанието на този документ се

генерира с безвреден за Вашия компютър active content (javascript)

> Ватопедският манастир в Св. Гора Атон

Scholars regard the Holy and glorious Great Monastery of Vatopaidi as one of the finest masterpieces of Byzantium in the world in terms of its superb architecture, which blends into a geographical setting of the greatest beauty. Seen in relation to the deeply-rooted tradition of its thousand years and more of life, it is generally admitted by experts and scholars to constitute a face of the triptych of that race in which that culture was continued and concentrated in the post-Byzantine period - a culture which has already perfected the Parthenon, the expression of the essence of ancient Greece, and Aghia Sophia - the Church of Holy Wisdom – the centre of Byzantium’s greatness.

We glorify the Triune God and thank the All-pure Blessed Virgin, the Custodian and Protector of this sacred place and particularly of our Great Monastery, preserved by the Mother of God, that it has been vouchsafed to us, its latest inhabitants, three years after the restoration of coenobitic life, to offer to the members of the Church this modest publication for their strengthening and spiritual benefit, but also to acquaint them with this glorious heritage of the land of Athos. In this way, a fervent wish, often expressed insistently, of the host of pilgrims to our revered Monastery has been fulfilled.

The need for the publication of this ‘pilgrim’s guide’, which is also an introduction to the major publishing enterprise planned - with the help of God - by the Monastery, taking the form of a series of devotional, historical and academic works and publications dealing with the wealth of its inherited treasures, was appreciated by a number of our predecessors, Fathers noted for their learning, who, as can be seen from the works which they have left, studied our archives in depth, such as the Elder Arkadios of Vatopaidi, who was a pupil of St Nektarios at the Rizarian School and who wrote a lengthy and as yet unpublished account of the glorious history of our Holy Monastery, and the Elder Theophilos of Vatopaidi, who drew up a short chronicle of the Monastery. It is their work which we are continuing today, by the grace of God, in publishing this pilgrim’s guide, which is the work of the brethren of the Monastery.

We owe our thanks to the A.G. Leventis Foundation for the financing of the guide, in the form of the noble institution of the benefaction, which by this gift has demonstrated its sensitivity to the immense importance of the cultural heritage of our race and its faith in the Orthodox tradition as the only ark of salvation which can afford deliverance to modern man, who is tormented on the false paths which he has followed.

All those who have in any way assisted in the success of this publication are deserving of our thanks.

I conclude this prologue at Vatopaidi on the 23rd of April, the day of the commemoration of the holy and glorious\ saint martyr George the Trophy-bearer, in the year 1913.

Archimandrite Efrem

Abbot of the Holy and Venerable Great Monastery of Vatopaidi

The Great and Holy Monastery of Vatopaidi stands on a picturesque stretch of coastline on the gulf of the same name and almost in the centre of the north-eastern side of the Athos peninsula, five minutes from the sea.

According to Athonite tradition, the Monastery was built by the Emperor Constantine the Great (324-337), was subsequently destroyed by Julian the Apostate (361-363) and was re-founded by the Emperor Theodosius the Great (379-395) as a thank-offering to the Blessed Virgin for saving his son Arcadius from certain death by drowning when, as a child, he was in peril in a rough sea near Mount Athos. Arcadius was carried in a miraculous manner to the shore, where the sailors found him sleeping near a bramble bush (Greek: pcnoq). For this reason the Monastery was called Vatopaidi: from fiaioq and naidiov (= a child). The spelling ‘Vatopedi’ is based on a derivation from fiaToqand ns5iov(= a plain).

The same tradition then takes us to the 10th century, when Arab pirates looted and burnt down the Monastery, slaughtering the monks and taking away with them to Crete as a prisoner the sacristan, the deacon-monk Sabbas (for an account of this event, which is connected with the icon of Our Lady Vimatarissa).

The biographer of St Athanasius the Athonite (second half of the 10th century) mentions three nobles from Adrianople, Athanasius, Nicholas and Antonius, who have a direct link with Vatopaidi. These came to Athos, bringing with them their fortunes, which amounted to 9,000 gold pieces, with the intention of founding a monastery. St Athanasius, knowing that the Monastery of Vatopaidi was in ruins as a result of the incursion of the pirates, sent them there to restore it. In fact, in a document dated 985 of the Protos* Thomas, we encounter the signature of the monk Nicholas as Abbot of the Monastery. This is the oldest official written evidence of its existence.

Monastery documents of the years 999 and 1002 tell us of a dispute between Vatopaidi and the Philadelphou Monastery, since the latter had been built near Vatopaidi, encroaching upon its boundaries. It would seem that Philadelphou was founded during the period when Vatopaidi had been laid waste by the Arabs and Abbot Nicholas protested to the Protos Nicephorus, laying claim to ownership of the Philadelphou Monastery. The documents in question cedes the Philadelphou Monastery to Vatopaidi, and the tradition that the three nobles from Adrianople did not found, but restored the Monastery of Vatopaidi when it was in ruins as a result of the pirate raid thus receives some confirmation.

The subsequent growth of the Monastery was rapid: in the Typikon* of Monomachus (1045), it took second place in the hierarchy of all the monasteries of the Holy Mountain, a position which it has retained until the present. It also gained the right to take part in the Synaxeis* in Karyes in the person of its Abbot and four delegates, to keep a yoke of oxen to ensure bread supplies and to have a boat for its needs.

In the years which followed, by acquiring a large number of metochia*, Vatopaidi began to expand both within and outside the bounds of Athos. The Monasteries of leropatoros,

Berroeotou, Kaletze, Xystrou, Tripolitou, Chalkeos and Trochala were soon annexed to it, as were the metochia of Prosphorion, Peritheorion, Chrysoupolis, St Demetrius at Cassandra

and two others near Thessaloniki, all of them outside the bounds of the Athos peninsula. It also obtained the regard of Byzantine emperors: Constantine Monomachus (1042-1055)

devoted to it each year 80 gold hyperpyra* from the imperial treasury. During the reign of Alexius Comnenus (1081-1118), the Monastery lost many of its metochia as a result of the

frequent wars; for this reason the Emperor ceded to it the Monastery of Sts Cosmas and Damian at Drama.

At the end of the 12th century, the former prince of Serbia Symeon

Nemanja and his son Sabbas, subsequently the first Archbishop and Ethnarch of Serbia, were monks of Vatopaidi. The presence of these two saints lent great prestige to the

Monastery, and to Athos as a whole. St Sabbas took part in official missions to Constantinople in order to settle issues concerning the Holy Mountain. It was on his request that

the Monastery ceded to the Serbian saints the “melissomandrion” (= apiary) of Chelandari, so that they could build the Serbian monastery of that name. Their presence at Vatopaidi

and their benefactions to it were always to remain in the memory of the Serbian people, and all the Serbian princes served as protectors and benefactors of the Monastery.

It was in the time of St Sabbas that the Monastery flourished as never before or after. It had as many as 800 monks, extended its buildings, thanks to the efforts of the two saints, and founded five new chapels on the site. With the founding of the Chelandari (or ‘Chilandari’) Monastery, a kind of spiritual affinity between the two brotherhoods developed. This has meant that the custom has survived down to the present for the representatives of Chilandari to play a prominent role at the Feast of the Vatopaidi Monastery (25 March) and those of Vatopaidi at that of Chilandari (21 November).

During the period of Frankish rule, the Monastery’s development was suspended and progress came to a halt. The pirate fleet of the Catalans plundered and laid waste the monasteries, forcing the monks to reveal the hiding places of their treasures. In those difficult times, the Monastery lost many of its precious objects and documents.

After the unsuccessful attempt of the Emperor Michael VIII Palaeologus (1259-1282) to bring about the reunion of the Eastern and Western Churches at the Council of Lyons (1271), the Monastery suffered fresh tribulations. According to tradition, when the supporters of the union returned from Lyons, they invaded the Holy Mountain and attempted to force the monks to embrace their views. The refusal of the Vatopaidi brotherhood resulted in the hanging of the Abbot Euthymius and the drowning of 12 monks in the bay of Kalamitsi, as well as the hanging of the Protos of Karyes, St Cosmas of Vatopaidi.

Shortly afterwards, however, with the aid of the Palaeologues, the Monastery recovered. Andronicus II (1282-1328) regarded it as “from time immemorial among the first and the glorious” and provided it with financial support so that it could return to its “former prosperity and state”.

The attacks of the Catalans were succeeded by those of the Turks, with the result that some of the monasteries were devastated and that the ascetics who had been scattered all over the Holy Mountain gathered in the large monasteries, in order to escape ill-treatment at the hands of the Turks. Vatopaidi, with its high walls and nine towers, was an impregnable fortress and a safe refuge for the monks. At the same time, the Blessed Virgin was an ever-vigilant guardian and protector of the Monastery, as is shown by the miracle at that period of known as the ‘Paramythia’.

In 1347, the Emperor John VI Cantacuzene (1347-1354), at the request of the monks of Vatopaidi, dedicated to their Monastery that of the Psychosostria in Constantinople, so that those monks of Vatopaidi who were visiting the capital could find “rest and domicile and any other due security”. The Emperor himself visited the Monastery a little before 1341 and presented the library with 26 elegantly decorated codices and a gold-embroidered epitaphios*. He also built within the Monastery the tower of St John the Divine and, outside it at a short distance, the tower of Kolitsou. So great was Cantacuzene’s love and concern for Vatopaidi that in the last years of his life he retired there and was tonsured a monk under the name of Joasaph. His name is commemorated even today among the ‘proprietors’ (ktetores) of the Monastery and tradition has it that he was buried in the katholikon. The rooms which stand near the Chapel of St John the Divine are reputed to be where the Emperor lived.

Apart from Cantacuzene, the Monastery numbered among its monks other princes, such as Andronicus Palaeologue, Despot of Thessaloniki (the monk Acacius), and the monk Gabriel (Palaeologue) (1432).

At the same time, it attracted to it, or the area around it, certain major ascetics. Prominent among them are the figures of St Gregory Palamas, the great hesychast theologian, and his teacher St Nicodemus, St Joasaph of Meteora, and St Sabbas, the ‘fool for Christ’s sake’, whose life was written by his pupil St Philotheus Coccinus, Patriarch of Constantinople, stand out. These were followed a little later by St Macarius Macres, subsequently Abbot of the Pantocrator Monastery in Constantinople (1431), while during the early years of Turkish rule it sheltered for a while the former Ecumenical Patriarch, Gennadius Scholarius.

Around the year 1500, another Patriarch of Constantinople, St Niphon, accompanied by his disciples the martyrs Macarius and Joasaph, betook himself to the Monastery. It was at this period also that the polymath St Maximus the Greek, the great missionary to the Russians, was a monk at Vatopaidi. According to the latter’s testimony, the Monastery at that time followed a semi-coenobitic way of life; it functioned, that is to say, as a lavra*. The oldest act converting it into a coeno-bium at this period dates from 1449. How long it remained idiorrhythmic is unknown.

In this connection it should be pointed out that because of the many adversities suffered by the monasteries during the 14th century, they were forced to adopt the idiorrhythmic system so as to leave the monks free to earn their own livelihood. However, they retained the institution of the abbot, whose duties were chiefly spiritual. The powers of administration were committed to the dikaios* of the monastery. The first Dikaios of Vatopaidi is encountered in a document of 1316 the priest-monk Niphon. After the office of dikaios, that of the sacristan was introduced. The latter managed the monastery’s property, while the dikaios now concerned himself with its affairs in the outside world. The monk Ignatius is the first Sacristan of whom we hear -in a document of 1633. In the year 1574, the Monastery was again converted into a coenobium, on the initiative of Silvester, Patriarch of Alexandria.

Raids by pirate ships continued without abatement, resulting in the looting and devastation of the monasteries. Faced with this danger, Vatopaidi sought protection from Western princes, some of whom responded favourably, such as Alfonso, King of Spain (1456), William, Marquis of Monferrato (1512) and Francesco Morosini, Grand Captain of the Republic of Venice (1664). All of these issued orders placing the Monastery under their protection and threatening raiders with fines. Pope Eugenius, moreover, in a letter of 1439 urged Roman Catholics to visit the Monastery and support it financially.

The period of Turkish rule was one of many tribulations for the Monastery, one of the worst blows being that it lost a number of its metochia, which were expropriated by the Turkish pashas. In a firman* of 1516 the only metochia of the Monastery listed are: Prosphorion (today’s Ouranoupoli), Ammouliani, Provlakas, Ormylia, St Mamas at Serres, Zavernikeia, St Panteleimon, Prinarion on Lemnos and some houses in Thessaloniki. Other documents of the same period mention the metochia of St Nicholas at Vistonida and of St Phocas in Chalcidice.

The loss of large numbers of estates and metochia reduced the Monastery to dire economic straits: in 1610 it owed 81,000 aspers* to the governor of Sidirokafsia. When the timelimit for payment had passed without the Monastery being able to pay off its debt, the governor sold to the monks of Pantocrator the kellia* called ‘Yiftadika’ for 71,000 aspers. Finally, Scarlatus Grammaticus, steward to the Prince of Moldo-Wallachia, intervened and gave the Vatopaidi monks 70,000 aspers to buy back these kellia.

In this difficult period, the Tsars of Russia proved very helpful, as did the Princes of the Danubian Provinces, who ceded to Vatopaidi the monasteries of Golia (1604), Pretzista (1646), St Nicholas (1667), Barboio (1669) and Myrra (1689), as well as the sketes of Grazdeni, Fatatzouni, Kanitzou (1690) and Raketossa (1729). In the mid 19th century, the Monastery had some 45 metochia in Bessarabia with vast tracts of arable land, yielding income which in the last years in which they were held amounted to 26,800 Ottoman pounds. Unfortunately, however, the Monastery lost these metochia as well, since in 1863 Prince Cuza seized them and drove out all the monks.

Able fathers from the Monastery were sent to these metochia to rule them as their abbots and to manage their property. Some of them, moreover, were renowned for the virtue of their lives and for the influence which they exercised at the courts of the princes in the interests of the enslaved Greek race. The Ecumenical Patriarchate, in appreciation of their work, consecrated them bishops, their title being ‘Metropolitan of Eirenoupolis and Vatopaidi’.

The setting up of the Athonite School in 1748 was Vatopaidi’s greatest contribution to the interests of the enslaved nation. The building of the School and its operation were undertaken in full by the Monastery -at a period when it faced major economic problems because of the crippling taxation imposed by the Turkish authorities.

The founding of the School gave a fillip to the morale of the Greek world in its shackles, engaging the imagination and feelings of patriarchs and men of letters, so that Adamantios Koraes, in extolling the monks of Vatopaidi, wrote: “Felicitations, and again felicitations, most venerable fathers of Vatopaidi. Although you have paid what you owed to our homeland, it should thank you as benefactors and not as those who pay what they owe…” (Koraes, Parallel Lives of Plutarch, vol. A2, p. 937).

The Athonite School was the biggest Greek school in the Greek world under Turkish occupation, the number of pupils reaching 200. Its first headmaster was the deacon-monk Neofytos Kafsokalyvitis. In 1750, the Patriarch of Constantinople, Cyril V (1748-1757), issued a sigillium* in which he announced to the Christian world the founding of the School and sought financial support for it. At the same time, the Monastery sent to Thessaloniki the priest-monk Joasaph with sacred relics to collect subscriptions for the School. After the resignation of Neofytos, the running of the School was taken over by the ‘Great Teacher of the Nation’ Evyenios Voulgaris, while the teachers included the deacon-monks Kyprianos Kyprios, afterwards Patriarch of Alexandria (1766-1783), Nikolaos Tzertzoulis and Panayotis Palamas. Among the more famous of the School’s pupils were St Cosmas of Aetolia, the national hero Righas Ferraios, the scholar and writer Sergios Makraios, the educationalist losipos Misiodax, and the theologian Athanasios of Paros. St Nicodemus the Athonite and Adamantios Koraes were among those who toiled to ensure its smooth operation.

After Voulgaris left, the School was never again to regain its former glory, with the result that around the year 1811 it ceased to function and during the years of the War of Independence, fell into ruins. Of these ruins, the only building to have survived down to the present is the Chapel of the prophet Elijah. A small school, however, continued to operate within the confines of the Vatopaidi Monastery to serve the needs of its brethren, with educated monks as its teachers. In 1821, the brotherhood of Vatopaidi made a last effort to convert their monastery into a coenobium. They communicated this resolve in a letter to the Ecumenical Patriarchate, seeking that a sigillium should be issued to this effect. However, the proclamation of the Greek Revolution intervened and the effort came to nothing. The Holy Mountain entered a fresh period of turmoil, which was to last until 1830.

To the national struggle the monasteries contributed their cannons, ammunition, and victuals, and turned their smithies to the production of weapons. One thousand, five hundred monks, led by the captain Emmanouil Pappas, drove the Turks out of Chalcidice. The Vatopaidi Monastery, on the request of the Holy Community, fitted out a ship with provisions and sent it to Provlakas in support of the army. The uprising was, in the end, a failure and the army was scattered over Mt Pangaio and in the trenches of Vigla.

The danger was now manifest, and Vatopaidi urged the other monasteries and the Holy Community to send senior monks as delegates to Provlakas to parley with the Turkish army. A large delegation, consisting of 120 senior monks, went to Provlakas and persuaded Abdul Rubut Pasha to negotiate, on condition that the monasteries should pay 1,500,000 piastres* as war reparations. Since, however, it was impossible to find so large a sum immediately, they asked the Pasha to accept 1,000 poungeia* as a prepayment and the rest by a given date. The Pasha accepted this arrangement, but held the 120 delegates as hostages. Of these, 82 were taken to prisons in Thessaloniki and Constantinople, where the majority died from illtreatment.

After this agreement had been reached, Rubut Pasha sent 3,000 troops to the Holy Mountain, headed by Murat Aga, in order to take charge of weapons and ammunition and to arrest the revolutionaries. The Turkish soldiers went from monastery to monastery, demanding food for themselves and their horses. The rest of the monasteries turned to Vatopaidi for help, asking for rice and barley and calling its monks their saviours. These tribulations of the Athonites came to an end with the withdrawal of the Turkish troops on 13 April 1830, the Sunday after Easter.

The years which followed, however, were no less difficult, and the Monastery fell into destitution because of heavy taxation and the loss of its metochia. It was forced to sell a large number of properties in order to pay off its debts; many of its metochia were illegally occupied by the Turks. All that was left were the revenues from the metochia in Wallachia and Bessarabia, and these too were confiscated by the Romanian State in 1863.

In spite of all this, Vatopaidi continued in more modern times to give generously to philanthropic causes. In 1880, the Monastery donated 3,700 pounds for the building of the Great School of the Nation and in 1908 gave the sum of 5,000 pounds to the Theological School of Chalki. In 1912, it undertook the building of the School of Languages in Constantinople.

In 1906, at the request of the Greek Consul in Thessaloniki and the Ecumenical Patriarchate, the Monastery bought the Souflar metochi at Kalamaria, which then belonged to the Jew Jacob Modiano, so that it should not fall into alien hands. To the city of Thessaloniki itself, after the 1917 fire, Vatopaidi gave the considerable sum of 50,000 gold francs for disaster relief, and in the same year contributed what was for the time the large sum of 20,000 drachmas to the French Red Cross. In 1912, it redeemed from the Turkish Aga two villages in Chalcidice, Vrasta and Stavros, for the sum of 8,000 pounds. The Monastery’s philanthropic interests extended as far as Cyprus, where in 1860 it built a school in the village of Pedoula and in 1915 provided 1,000 pounds for the setting up of the ‘Vatopaidi School’ in Larnaca.

In June 1930, the work of the preliminary committee of the Orthodox Churches was carried out on the Monastery premises by representatives of the Autocephalous Churches under the chairmanship of the Metropolitan of Heracleia, Filaretos Vafeidis. In the following year, the Prime Minister of Greece, Eleftherios Venizelos, paid an official visit to the Monastery and was accorded a welcome of some grandeur. In his honour, the famous carpet, with the Monastery’s monogram and the double-headed eagle, stretched from the harbour to the main church. This carpet, measuring 700 metres, was made in 1913 for use during the visit of King Constantine to Mount Athos, a visit which never, in fact, took place.

During celebrations for the thousandth anniversary of the Holy Mountain in 1963, the Monastery was visited by the then Ecumenical Patriarch, Athenagoras, King Paul and other distinguished guests.

A decisive point in the Monastery’s recent history was its remanning in 1987 by a group of monks led by the elder Joseph Spilaiotis (’the cave dweller’), from Aghiou Pavlou Monastery’s Nea Skete. Moreover, following a resolution on the part of the fathers of the Monastery and with a sigillium from the late Ecumenical Patriarch, Demetrius I, in 1989 the Monastery returned, after the elapse of centuries, to the coenobitic system of life. Archimandrite Ephraim was elected as first Abbot, and his enthronement took place on the Second Sunday after Easter (29 April) 1990.

The Vatopaidi Monastery is regarded as the largest group of buildings in area and volume on Mount Athos. For this reason, from the very earliest years of its existence it has borne the title of the Megiste (’very great’) Monastery of Vatopaidi. In documents of the 11th century it is encountered as the ‘Lavra of Vatopaidi’ and in others of the 14th century as ‘the Great Monastery of Vatopaidi’.

From the outside, the Monastery is polygonal in appearance and its enceinte, strongly reminiscent of a fortress, has at various points battlements and three defensive towers. The buildings standing today are representative of every period since the Monastery’s foundation, a fact due to the many rebuildings which have taken place, either to make good damage caused in a variety of ways, as, for example, by pirate raids or serious fires, or for purposes of expansion to meet new needs created by what has usually been the large number of Vatopaidi monks.

Of its outer sides, the north, parallel with the sea, was built in 1654 and is of a length of some 200 metres. This accommodates the Abbot’s quarters, the synodikon*, the secretariat, the old library, monks’ cells and what is today the guesthouse, the latter having been built in 1782 in the place of one of the nine towers which the Monastery originally had. The central section, which was burnt down and rebuilt recently, houses the new library and the icon storeroom.

The south-eastern side was rebuilt in 1818 and, apart from cells and various other buildings, contains the infirmary and accommodation for the aged, provided in 1856 in a two-storey building behind the sanctuary of the main church (katholikon). The enceinte is completed by the western side, built in its present form in 1864.

It is at the lowest point of this side that the great gate of the Monastery opens. This is approached by ascending many flights of semicircular steps on the rising ground. Entry is by a double gate, closed every night with two massive, ironclad wooden doors. Above the first of these, protected by a glass-encased vault is the icon of Our Lady Pyrovolitheisa and next to it an inscription giving the date of the painting of the interior of the domed porch (1858).

As the visitor passes through the main gate, he emerges into the spacious paved courtyard, which contains various buildings, such as the refectory and the olive oil store in the foreground and the main church (katholikon) in the background. Incorporated into the katholikon are the clocktower and the phiale*, while next to it stands the belltower. Further on, to the south and west of the courtyard, are the new bakery, the quadruple fountain, the Chapels of Sts Cosmas and Damian and of the Holy Girdle, and the old bakery.

The katholikon of the Vatopaidi Monastery is an imposing building, dedicated to the Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin (feast day 25 March), which has remained virtually unaltered for 10 centuries. In terms of architecture, it follows the style of the katholikon of the Megiste Lavra Monastery, with minor deviations. It is divided into five parts:

The exonarthex is elongated and by means of a marble stairway connects the katholikon with the northern wing. In the middle of this stairway is the Paramythia Chapel, with the miracle-working icon of the same name. The two-storey, open exonarthex must have been added in the 17th century. Above the marble doorway of the entrance, leading to the exonarthex, is an inscription of 1426, which must be that of earlier repairs. The fresco of the exonarthex, which depict the 24 stanzas of the Akathistos Hymn*, warrior saints and the Second Coming, were repainted in 1843.

Three doors open on to the narthex. The central door is clad with bronze plates on which are embossed plant and other decoration, as well as a depiction of the Annunciation in relief. According to tradition, this door came from the Church of the Holy Wisdom in Thessaloniki and was brought to the Monastery after the city was taken by the Turks (1430). The other two doors lead to the Chapels of St Nicholas and St Demetrius, respectively, on the right and left of the lite. Over the door of the Chapel of St Nicholas is a depiction of the Saint in mosaic (14th century), in a rather poor state of preservation. On the right is a large fresco of the Blessed Virgin holding the Holy Child. This fresco replaced the miracle-working icon of the Paramythia, which after the miracle was removed to the chapel of the same name.

Also to be found in the exonarthex, built into the walls, are Byzantine parapets and reliefs from the ancient city of Thyssos, which stood on the site of Vatopaidi. The reliefs bear the forms of marine deities, such as the Titan Crius.

The lite, an area created to meet the liturgical needs of monasteries, takes its name from the service of the same name conducted in it. On the pilasters of the arches to the right and left of the central door and above the door itself can be seen the famous mosaics with their depictions of the Annunciation (early 14th century) and the Deisis* (late 11th, early 12th century) – the only mural mosaics to be preserved anywhere on the Holy Mountain. The wall painting of the lite -and, indeed, of the whole katholikon- was carried out, according to an inscription of a later date, in the reign of Andronicus II Palaeologue, in 1312, but has been painted over on many occasions. In spite of this treatment, the frescosmurals remain masterpieces of the so-called Macedonian School and are attributed to pupils of Panselinos. This attribution is lent particular support by the series of scenes from the Passion and by various other sections which have escaped repainting.

Further back on the left, in the narthex of the Chapel of St Demetrius, the miraculous icon of the Theotokos which bears the name of Esphagmeni is painted on the wall.

This area, between the lite and the main body of the church, takes its name from the night service held in it. At the back, on the right, a tomb of the mid-Byzantine period is preserved, built into the wall. According to tradition, it contains the relics of the Monastery’s founders, Athanasius, Nicholas and Antonius, a tradition completely confirmed when the tomb was opened recently. These three figures are portrayed above it in a mural, together with the Emperors Theodosius the Great, Arcadius, Honorius and John Cantacuzene. At the back on the left can be seen, in a fresco, the miraculous icon of Our Lady Antiphonitria.

The mesonyktikon, which, it should be noted, takes this form only at Vatopaidi, was painted in the year 1760.

This, the main body of the katholikon, preserves for us all the grandeur of Byzantine taste: a magnificent floor, porphyry columns, frescos (see the lite) and mosaics, a carved and gilt wooden iconostasis, innumerable silver and gilt hanging lamps and silver candelabra.

The main door of the nave, dating from 1567, is the work of the monk Lavrentios. Made of ebony and silver, it is of very fine workmanship, with an impressive arrangement of decorative designs.

The floor dates from the 10th century and is beautifully inlaid with multicoloured marble. Tradition relates that the four great columns of the central dome, of porphyry, were brought from Italy. Immediately above the columns on the east is a depiction of the Annunciation in mosaics, divided into two, which dates from the mid 11th century.

The carved wooden iconostasis, of oak, dating from 1788, replaced an older one of marble, a part of which remains in its original position. The large icons on the screen, work of the Palaeologue era, were gilded by Count Dmitri Nikolayievitch Seremetiev in 1857. In front of the two eastern columns are shrines with fine Byzantine icons of Our Lady Hodegetria and the Hospitality of Abraham. According to tradition, these icons came from the Church of Holy Wisdom in Thessaloniki. Above the abbatial throne on the left (1619) is an icon of the 14th century depicting Sts Peter and Paul, a gift of the Despot Andronicus Palaeologue (1421).

From the central dome hangs the great silver candelabrum, with its vast number of candle and lampholders. It was made in Vienna in 1882 and replaced an older brass one which today hangs in the lite. The two smaller candelabra, given by the people of Santorini, were made in Moscow in 1832.

The sanctuary contains a number of important sacred treasures of the Monastery. First among these is the icon of Our Lady Vimatarissa or Ktitorissa, which is in a marble shrine on the synthronon* behind the altar. Opposite the icon and on the altar is the cross of Constantine the Great, and, on the right, the silver-overlaid candle, which St Sabbas, the sacristan, hid together with the icon in the well of the sanctuary for 70 years.

The sanctuary is also decorated with a large number of fine icons and with the votive offerings of various personages. Among those deserving particular mention are the old icons of the Hodegetria and the Archangel Gabriel, both of the 14th century, and the miniature icons of the Blessed Virgin and of Christ, the so-called ninia (= little children) of the Empress Theodora, given by Anna Palaeologina Cantacuzene. What, however, is regarded as the Monastery’s priceless treasure is the Girdle of Our Lady, which is preserved in separate pieces in three gilt cases. Amongst other highly valued objects are two cases, one containing a large piece of the True Cross and the other a piece of the reed which the Jews gave to Christ in mockery at the Crucifixion.

Some 200 other holy relics are contained in a host of extremely valuable silver reliquaries. Among these are the skulls of St John Chrysostom, St Gregory the Theologian, St lakovos the Persian and St Mercurius, and parts of the skulls of Sts Sergius, Florus, Pelagia, Theodosia, Arethas, Theodore the Warrior and St Damian, the metopic bone of the Apostle Andrew, a part of the right hand of the martyr St Catherine and of St Stephen the Protomartyr, as well as relics of Sts Parasceve, Marina, Artemius, Gregory of Decapolis, Procopius and Tryphon. Also preserved complete are the remains of St Evdokimos of Vatopaidi, which were discovered in 1842 while the cemetery church was being restored. Also in the sanctuary are the skulls of the Patriarchs of Constantinople Maximus IV (1491-1497) and Cyprianus (1707-1714), and of the Patriarch of Antioch Gerasimus (1884-1891), who died and were buried at the Monastery.

Opposite the entrance to the church stands the Monastery’s imposing refectory. It is built in the shape of a cross and was restored, according to the surviving inscriptions, in the years 1314, 1526 and again in the 18th century. The wall paintings were executed in 1786. The refectory contains 30 horseshoe-shaped marble tables, which, according to tradition, come from the famous Studium Monastery in Constantinople. At the west end, under a vault painted with a depiction of the Platytera (’Broader than the Heavens’), is the Abbot’s table, which directly faces the altar of the katholikon.

The upper floor of the refectory has been recently laid out as a small guesthouse, where old engravings, porcelain and folk art objects are on display.

South of the refectory and very close to it stands the olive oil store, where the Monastery’s supply of olive oil is stored in large ceramic jars or marble cisterns. The exact date of the building is unknown, but its facade is known to have been put up by the Abbot Theophanes in the year 1627. In this building the small, miracle-working Byzantine icon of Our Lady Elaiovrytissa is kept. Also in the storeroom are two marble sarcophagi, today used to hold oil, one with an inscription with the name of Dionysius and the other, dating from 321 AD, with that of Germanus Heraclas.

The original phiale* for holy water was built at the expense of Matthew Cantacuzenus (1354-1357). The one in use today is a small circular building dating from the early 19th century. It communicates with the exonarthex of the katholikon and is formed by a double colonnade, of which the outer columns on the north and south sides have low parapets between them. The basin stands in the centre, sheltered by a dome decorated on the inside with frescos (1810) having baptism as their subject. On the first Sunday of every month, the icon of the Vimatarissa is brought here, together with the cross of Constantine, for the customary blessing of the waters, after which there is procession with the icon.

To the south of the phiale stands the Monastery’s bell-tower, at 35 metres, the highest on the Holy Mountain -and the oldest. It was built in 1427 and today houses eight bells. On the facade this inscription can just be made out:. “The bells above pealing joyously call the faithful unto praise of God. In the year 1427, indiction 5″.

The tower which is incorporated into the south-western corner of the church contains the great clock. The quarters are struck by a wooden negro with a metal hammer and the hours by a bell in the tower. The original clock was given in 1815 to the Pasha of Thessaloniki.

In addition to its main church, the Monastery has 31 chapels. Nineteen of these are among its buildings, and the rest lie round about it. Among the former are those of St Demetrius, St Nicholas, the Holy Trinity, the Archangels, and Our Lady Paramythia, all these being parts of the katholikon Three of these -St Demetrius (1721), St

Nicholas (1780) and the Paramythia (1678)- have wall paintings, the frescos of the latter having been painted at the expense of the Metropolitan of Laodicea Grigorios. The three towers of the Monastery contain the chapels of the Transfiguration, the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin, and of St John the Baptist. In the Monastery’s various wings there are chapels dedicated to St Andrew, St George, Sts Theodore, St Menas, the Three Hierarchs, St Thomas, St John the Divine, St John Chrysostom and St Panteleimon (in the infirmary).

Of particular interest are the Chapels of Sts Cosmas and Damian and of the Holy Girdle, which stand in the spacious courtyard. The former, according to tradition, was built by St Sabbas, Archbishop of Serbia, for the liturgical needs of the Monastery’s Serbian monks. In 1364, restoration by the Despot loannis Ugljesa gave it its present form. The first wall paintings were executed at the end of the 14th century; these were repainted in 1847. The floor has old marble inlays and on its eastern columns, the figures of Christ and the Blessed Virgin survive from the original frescos.

The Chapel of the Holy Girdle was built on the site of an older church dedicated to St Constantine, built by the Voivode Neagoe in 1526. The quaint chapel which we see today is a rebuilding by Theofilos Sozopolitis of 1794; the frescos were painted in 1860. The chapel contains two carved wooden lecterns which, tradition relates, were donated to the Monastery by the Despot Andronicus IV Palaeologue. On one of these the 24 stanzas of the Akathistos Hymn are depicted and on the other, scenes from the Old Testament. The gilt iconostasis of carved wood dates from the year 1816 and, from the point of view of artistic merit, is considered the third in rank on the Holy Mountain and the finest of the eight such screens in the Monastery.

The library and the archives of the Monastery are housed in the north-eastern tower, the Tower of Our Lady, as it is called, since on its first floor there is a chapel dedicated to the Nativity of the Virgin. In former times the library was housed above the iner narthex of the katholikon, in the so-called ‘place of the catechumens’, but the demands of safety and space were such that in the last century it was moved to the tower, which has four floors and now houses some 2,000 manuscript codices and a number of the 40,000 printed books.

The archives contain priceless chrysobulls issued by Byzantine emperors, patriarchal sigillia, wax bulls, documents originating with princes of Serbia, Bulgaria and the Danubian Provinces, Tsars of Russia and a wealth of firmans and berats issued by the Ottoman Sultans. It also has, because of the large number of metochia which the Monastery once held in Wallachia and Bessarabia, the largest Romanian archive (approximately 14,000 documents) on Mount Athos.

On display in a case on the ground floor are some of the Monastery’s most important codices:

a. the Geography of Ptolemy (codex 655), with 42 maps of Europe, Asia and Africa, the oldest copy of the kind in the world (13th century).

b. the Psalms of David (codex 761), a copy of the 11th century, with the signature of the Emperor Constantine Monomachus on the first leaf.

c. the Octateuch (codex 602) of the 13th century, the most richly decorated codex on the Holy Mountain, with 165 miniatures with scenes from the Old Testament.

d. Fragments from the four Gospels of the 6th—8th century in capitals.

e. A chrysobull of the Emperor Andronicus II Palaeologue (1301).

f. A palimpsest codex (the original text being of the 8th-9th century with sermons of St John Chrysostom on the First Epistle to the Corinthians, overwritten with a text of the 13th century) (codex 18).

Framed on the walls are firmans and berats of the Sultans of the Ottoman Empire and letters of appointment, that is, documents belonging to the various bishops who have been monks of Vatopaidi.

On display in the same area is the famous iaspis (=jasper), one of the Monastery’s most valuable treasures. This is a royal drinking cup, the gift of Manuel Cantacuzene Palaologue, Despot of Mystras (1349-1380), carved in the semi-precious stone from which it takes its name. This multi-coloured transparent stone was believed to have the property of turning water into an emulsion which was a specific against snake bites. According to old written sources, it was also used as a container for holy water, which had healing properties. The base of the cup is gilt and bears the monogram of the Despot, together with the figures of saints in relief.

Scattered around the Monastery are chapels, kathismata*, boathouses, storehouses and other buildings serving its needs. As the visitor lands from the sea, he first encounters the great arsanas*, which was built in 1496 by Stepan, Voivode of Moldo-Wallachia, and has a chapel dedicated to St Nicholas. Next to the arsanas is the wheat store, built in 1820 by the Voivode Skarlatos Kallimachis. As he climbs to the Monastery, the visitor sees on the right and left the following buildings: the flour mill (1869), the smithy (1884), the cemetery with the Chapel of the Holy Apostles (1683), the Chapel of St Modestus (1818) with accommodation for the Monastery’s lay workers, the stable and a garden building with a chapel dedicated to St Tryphon (1882). Last, in front of the outer gate of the Monastery (1822) there is a large kiosk (1780), while a second kiosk (1877), to the west, marks the site of a well at which, on the third day of Easter, the service for the blessing of the waters takes place, after which there is a procession with the wonderworking icon of the Vimatarissa.

The Vatopaidi Monastery has a large number of dependencies. Among these, the Sketes of St Demetrius and St Andrew are of particular importance.

The former lies half an hour’s walk from the Monastery, to the southwest, on the site of the small Chalceos Monastery, of whose existence there is evidence as early as the 10th century. According to tradition, it was built by relatives of St Demetrius. Marble work of the 12th century, part of the kyriakon*, is all that survives from the Byzantine era. It was organised as a skete in the 18th century, when its first typikon* was drawn up (1729). The wall paintings which adorn the interior of the kyriakon date from 1755 and those in the exonarthex, which was built later (1796), from 1806. The cemetery chapel was built in 1764.

The skete is idiorrhythmic and consists of 21 dwellings, most of them now in ruins.

The imposing Russian Skete of St Andrew (commonly called ‘Serai’) stands on a site once occupied by the small Xystrou Monastery. There was a kellihere dedicated to St Antony, when, after resigning their office, two Patriarchs of Constantinople, St Athanasius III Patelaros (1651) and Seraphim II (1761) took up residence on this spot. These Patriarchs successively restored the building and the church of St Antony, giving the kelli its present name. In 1842, the first Russian monks began to settle here. They extended the buildings and built the impressive Church of St Andrew. The /ce///was given the rank of a skete by a patriarchal sigillium of 1849, and in 1900, the former Patriarch of Constantinople loakeim III consecrated its kyriakon. This has a length of 60 metres, a breadth of 33, and a height of 29, and, as such, is one of the biggest churches in the Balkans. This skete, from the time of its foundation, followed the coenobitic way of life, and at one period had as many as 800 monks. The fire of 1956, which destroyed its western side and the gradual reduction in the number of monks in the first half of the present century resulted in it being abandoned. Today, the Athonite School operates in the southern wing of the skete.

Vatopaidi has 27 kellia scattered around it, some close at hand and others at a greater distance. Five of these are in Karyes, two on the spot called ‘Yiftadika’, and eight in the ‘Kolitsou’ area. This placename is derived from the old monastery of Kaletzi, whose high tower, built by the Emperor John Cantacuzenus, still stands today.

The Vatopaidi Monastery, from Byzantine times onwards, had a large number of metochia beyond the bounds of the Holy Mountain in the broader Balkan region. By means of these it met the needs of its large community and at the same time was in a position to make its contribution to national and philanthropic causes. Its metochia abroad were confiscated by the governments of the states where they were situated, and most of those on Greek territory (for example, those of Chalcidice, Ouranoupoli, Ammouliani, Nea Roda and Souflar) were given away free to shelter and provide a livelihood for refugees from Asia Minor. Today the Monastery still possesses the metocH of St Nicholas on the Vistonida lake, that of St Phocas in Chalcidice, and one other on the island of Samos.

The Girdle of the Blessed Virgin Mary, today divided into three pieces, is the only remaining relic of her earthly life.

According to tradition, the girdle was made out of camel hair by the Virgin Mary herself, and after her Dormition, at her Assumption, she gave it to the Apostle Thomas. During the

early centuries of the Christian era it was kept at Jerusalem and in the 4th century we hear of it at Zela in Cappadocia. In the same century, Theodosius the Great brought it back

to Jerusalem, and from there his son Arcadius took it to Constantinople. There it was originally deposited in the Chalcoprateion church, whence it was transferred by the Emperor

Leo to the Vlachernae church (458). During the reign of Leo VI ‘the Wise’ (886-912), it was taken to the Palace, where it cured his sick wife, the Empress Zoe. She, as an act of

thanksgiving to the Mother of God, embroidered the whole girdle with gold thread, giving it the appearance which it bears today.

The Girdle of the Blessed Virgin Mary, today divided into three pieces, is the only remaining relic of her earthly life.

According to tradition, the girdle was made out of camel hair by the Virgin Mary herself, and after her Dormition, at her Assumption, she gave it to the Apostle Thomas. During the

early centuries of the Christian era it was kept at Jerusalem and in the 4th century we hear of it at Zela in Cappadocia. In the same century, Theodosius the Great brought it back

to Jerusalem, and from there his son Arcadius took it to Constantinople. There it was originally deposited in the Chalcoprateion church, whence it was transferred by the Emperor

Leo to the Vlachernae church (458). During the reign of Leo VI ‘the Wise’ (886-912), it was taken to the Palace, where it cured his sick wife, the Empress Zoe. She, as an act of

thanksgiving to the Mother of God, embroidered the whole girdle with gold thread, giving it the appearance which it bears today.

In the 12th century, in the reign of Manuel I Comnenus (1143-1180), the Feast of the Holy Girdle on 31 August was officially introduced; previously it had shared the Feast of the Vesture of the Virgin on 1 July. The Girdle itself remained in Constantinople until the 12th century, when, in the course of a defeat of Isaacius by the Bulgar King Asan (1185), it was stolen and taken to Bulgaria, and from there it later came into the hands of the Serbs. It was presented to Vatopaidi by the Serbian Prince Lazarus I (1372-1389), together with a large piece of the True Cross. Since then it has been kept in the sanctuary of the katholikon. Under Turkish rule, the brethren of the Monastery took it on journeys to Crete, Macedonia, Thrace, Constantinople and Asia Minor, to distribute its blessing, to strengthen the morale of the enslaved Greeks and to bring freedom from infectious diseases.

The miracles performed by the Holy Girdle in various ages are innumerable. The following are a very few examples:

At one time, the inhabitants of Ainos called for the presence of the Holy Girdle and the Vatopaidi monks accompanying it received hospitality at the house of a priest, whose wife surreptitiously removed a piece of it. When the fathers embarked to leave, although the sea was calm, the ship remained immobile. The priest’s wife, seeing this strange phenomenon, realised that she had done wrong and gave the monks the piece of the Girdle, whereupon the ship was able to leave immediately. It was because of this event that the second case was made. The piece in question has been kept in this down to the present.

During the Greek War of Independence of 1821, the Holy Girdle was taken to Crete at the request of the people of the island, who were afflicted by the plague. When, however, the monks were preparing to return to the Monastery, they were arrested by the Turks and taken off to be hanged, while the Holy Girdle was redeemed by the British Consul, Domenikos Santantonio. From there the Girdle was taken to Santorini, to the Consul’s new home. News of this quickly spread throughout the island. The local bishop informed the Vatopaidi Monastery and the Abbot, Dionysios, was sent, in 1831, to Santorini. The Consul asked the sum of 15,000 piastres to hand over the Girdle, and the people of the island, with touching eagerness, managed to collect together the money. Thus the Holy Girdle was bought back and Abbot Dionysios returned it to Vatopaidi.

What had happen with the priest’s wife of Ainos was repeated in the case of the Consul’s wife. She too, un beknown to her husband, cut off a small piece of the Holy Girdle before it was handed back to the Abbot Dionysios. Within a very short period her husband died suddenly and her mother and sister became gravely ill. In 1839, she wrote to the Monastery asking that representatives should be sent to take possession of the piece which she had removed.

In 1864, the Holy Girdle was taken to Constantinople, since there was a cholera epidemic among the inhabitants. As soon as the ship bearing it approached the harbour, the cholera ceased and none of those already suffering from it died. This strange miracle excited the curiosity of the Sultan, who had the Girdle brought to the Palace so that he could reverence it.

During the time when the Holy Girdle was at Constantinople, a Greek of Galata asked that it should be taken to his house, since his son was seriously ill. When, however, the Holy Girdle arrived at his house, his son was already dead. The monks, however, did not give up hope. They asked to see the dead boy, and as soon as the Girdle was placed on him, he was raised from the dead.

In 1894, the inhabitants of Madytos in Asia Minor sought that the Holy Girdle should be taken there because a plague of locusts was destroying their trees and crops. When the ship carrying the Girdle came into the harbour, the sky was filled with clouds of locusts, which then began to fall into the sea, so that it was difficult for the vessel to anchor. The people of Madytos, seeing the miracle, kept up a constant chant of Kyrie eleison from the shore.

Down to our own times, the Holy Girdle has continued to work many miracles, particularly in the case of infertile women, who, when they request it, are given a piece of cord from the case holding the Girdle and, if they have faith, become pregnant.

This icon is on the synthronon* of the sanctuary of the katholikon and the

following tradition is associated with it.

This icon is on the synthronon* of the sanctuary of the katholikon and the

following tradition is associated with it.

In the 10th century, during the course of a raid on the Monastery by the Arabs, the deacon-monk Sabbas, who was sacristan (vimataris) at the time, managed to hide the icon in the well of the sanctuary, together with the cross of Constantine, placing a lighted candle in front of them. The Arabs plundered the Monastery and the deacon Sabbas was carried off as a prisoner to Crete. He gained his liberty 70 years later and returned to the Monastery, The younger monks, who knew nothing of the hidden treasures, opened the well on his instructions and found the icon and the cross standing upright on the water and the candle still burning.

This icon is also called Ktitorissa (from ktitor = founder), since its discovery took place during the time of the three founders of the Monastery, Athanasius, Nicholas and Antonius. In memory of this, a supplicatory canon to the All-holy Theotokos is sung every Monday evening, and every Tuesday, the Divine Liturgy is celebrated in the katholikon.

Another story is told of this icon. Once upon a time, one of the monks had difficulty in understanding the meaning of the verse “For a thousand years in thy sight are but as yesterday”, and was filled with sorrow that he could not find anyone to explain this to him. It so happened that at that time the former Patriarchs of Constantinople Cyril and Cyprian were staying at the Monastery and large numbers of monks from all over the Mountain had gathered to receive their blessing. On the Monastery’s patronal festival, the Annunciation of the Blessed Virgin, at the point when the Patriarch Cyril was going to reverence the sacred relics after the customary blessing, the monk heard a voice from the Vimatarissa icon explaining to him precisely the meaning of the verse, which caused him to thank the Blessed Virgin in tears for this miraculous solution to his difficulty.

This icon is a fresco of the 14th century which used to be in the exonarthex, in front

of the Chapel of St Nicholas, and was moved to a shrine in the chapel of the same name. In former times, there was a custom for the monks to kiss the icon as they came out of the

katholikon and for the Abbot to deliver the keys of the Monastery to the porter.

This icon is a fresco of the 14th century which used to be in the exonarthex, in front

of the Chapel of St Nicholas, and was moved to a shrine in the chapel of the same name. In former times, there was a custom for the monks to kiss the icon as they came out of the

katholikon and for the Abbot to deliver the keys of the Monastery to the porter.

Tradition relates that one day, in Byzantine times, as the Abbot was giving the keys to the porter, he heard the following words from the icon: “Do not open the gates of the Monastery today, but go up on to the walls and drive off the pirates”. The voice repeated the same words a second time. As he turned to look at the icon, he saw the

Holy Child putting His hand over the mouth of His Mother, saying “Do not watch, Mother, over this sinful flock; leave it to pass under the sword of the pirates, for its transgressions have multiplied.” But the Blessed Virgin, taking the hand of Christ and turning her head a little, repeated the same words. The monks immediately hastened to the walls and saw that pirates had indeed encircled the Monastery and were awaiting the opening of the gates in order to plunder it. The miraculous intervention of the Theotokos saved the Monastery, and the icon has preserved since then traces of the last movements of the figures. From that time on, the monks have kept a perpetually-burning lamp in front of the icon, celebrate in its honour the Divine Liturgy every Friday and chant a supplicatory canon in front of it every day. At one time it was customary for the tonsuring of monks to take place in this chapel.

Also associated with this icon is the life of the St Neophytus, who was ‘attendant’ of the same chapel. At one point, he was sent by the Monastery to serve for a period in a metochi in Evvia (Euboea). There he fell seriously ill and asked the Blessed Virgin to grant him that he should die in his home monastery. He immediately heard a voice telling him: “Neophytus, go to the Monastery and after a year you will be ready.” Neophytus thanked the Mother of God for this extension of his life and told his attendant to prepare for their return. A year later, after he had received Holy Communion and as he was climbing the stairs, Neophytus again heard the voice of the Mother of God, this time in front of the Chapel of the Paramythia, saying: “Neophytus, the time of your departure has come.” On going to his cell, he fell ill, and, having asked and received forgiveness from all his brethren, yielded up his spirit.

This icon is a fresco of the 14th century and is in the narthex of the Chapel of St

Demetrius. Tradition relates that a deacon who was the sacristan of the katholikon used to arrive at the meal in the refectory somewhat late every day, because of his duties. One

day, when he asked the monk in charge of the refectory for food, he was refused. The sacristan returned to the church, full of anger and indignation, and said to the icon: “How

long do I have to go on serving you and toiling, while you do not care even that I should eat?”, and, with that, he took a knife and plunged it into the face of the Blessed Virgin,

from which blood began to run, while he himself was struck blind and fell down like a madman. He remained in that state for three years, occupying a stall opposite the icon, where

he wept and implored the Mother of God to forgive him. After three years, the Blessed Virgin appeared to the Abbot and told him that she had forgiven the reckless sacristan and

would restore his health, but that the hand which had committed the sacrilege would be condemned at the Second Coming of the Lord. When the monk died and the time came, according

to the customs of the Holy Mountain, for the disinterring of his remains, it was found that although the rest of his body had decomposed, his right hand had remained intact and was

completely black. The hand of the sacristan is preserved today in the katholikon, but in a very delapidated state, since Russian pilgrims were given to taking small pieces of it,

under the impression that it was a sacred relic.

This icon is a fresco of the 14th century and is in the narthex of the Chapel of St

Demetrius. Tradition relates that a deacon who was the sacristan of the katholikon used to arrive at the meal in the refectory somewhat late every day, because of his duties. One

day, when he asked the monk in charge of the refectory for food, he was refused. The sacristan returned to the church, full of anger and indignation, and said to the icon: “How

long do I have to go on serving you and toiling, while you do not care even that I should eat?”, and, with that, he took a knife and plunged it into the face of the Blessed Virgin,

from which blood began to run, while he himself was struck blind and fell down like a madman. He remained in that state for three years, occupying a stall opposite the icon, where

he wept and implored the Mother of God to forgive him. After three years, the Blessed Virgin appeared to the Abbot and told him that she had forgiven the reckless sacristan and

would restore his health, but that the hand which had committed the sacrilege would be condemned at the Second Coming of the Lord. When the monk died and the time came, according

to the customs of the Holy Mountain, for the disinterring of his remains, it was found that although the rest of his body had decomposed, his right hand had remained intact and was

completely black. The hand of the sacristan is preserved today in the katholikon, but in a very delapidated state, since Russian pilgrims were given to taking small pieces of it,

under the impression that it was a sacred relic.

Another story about this icon relates that a priest, visiting the Monastery, questioned the truth of the miracle related above, but when he put his finger into the point where the icon had been damaged, it immediately ran with blood. The priest was aghast and fell down dead before he was able to leave the katholikon.

This too is a wall

painting, in the mesonyktikon of the katholikon. It is so named because a voice was heard from it (antiphonise = ‘it answered back’). Tradition relates that the Monastery was once

visited by the Empress Placidia, daughter of Theodosius the Great. While she was approaching the katholikon with the intention of entering by the small side door, she heard a voice

coming from the icon: “Stay where you are and come no further. How dare you, a woman, come to this place?”. The Empress, overcome with fear, asked forgiveness from the Mother of

God and left the Holy Mountain immediately. To commemorate this miracle, she paid for the building of the Chapel of St Demetrius.

This too is a wall

painting, in the mesonyktikon of the katholikon. It is so named because a voice was heard from it (antiphonise = ‘it answered back’). Tradition relates that the Monastery was once

visited by the Empress Placidia, daughter of Theodosius the Great. While she was approaching the katholikon with the intention of entering by the small side door, she heard a voice

coming from the icon: “Stay where you are and come no further. How dare you, a woman, come to this place?”. The Empress, overcome with fear, asked forgiveness from the Mother of

God and left the Holy Mountain immediately. To commemorate this miracle, she paid for the building of the Chapel of St Demetrius.

The icon of the Eleousa is kept in the same chapel, above the shrine on the left. It dates from the 15th century and comes from the Russian Skete of St Andrew, from which it was recently brought to the Monastery. According to information given by Gerasimos Smyrnakis, the icon was at one time built into the wall of a mosque in Constantinople which had formerly been a Christian church. It was discovered by some Christian workmen who were repairing the mosque in 1893 and secretly sold to Sofronios, the steward of the Skete’s metochiin Galata. From there it was brought by Russian monks to Mount Athos and placed in the kyriakon of the Skete of St Andrew.

This icon dates from the 14th century and is in the Monastery’s oil store. From there it is taken to the katholikon on the Friday after Easter, its feast day.

Tradition relates the following miracle: at a time when there was a shortage of olive oil in the Monastery, the St Gennadius, who was in charge of the Monastery’s oil supplies,

began to economise by giving oil only for the needs of the church. The cook, however, complained to the Abbot, who ordered Gennadius to be unsparing in giving oil to the

brotherhood, putting his trust in the providence of the Lady Theotokos. The Blessed Gennadius went one day to the storeroom and saw the tank running over with oil, which had

reached the door. From that time, the icon has emitted a remarkable fragrance.

This icon dates from the 14th century and is in the Monastery’s oil store. From there it is taken to the katholikon on the Friday after Easter, its feast day.

Tradition relates the following miracle: at a time when there was a shortage of olive oil in the Monastery, the St Gennadius, who was in charge of the Monastery’s oil supplies,

began to economise by giving oil only for the needs of the church. The cook, however, complained to the Abbot, who ordered Gennadius to be unsparing in giving oil to the

brotherhood, putting his trust in the providence of the Lady Theotokos. The Blessed Gennadius went one day to the storeroom and saw the tank running over with oil, which had

reached the door. From that time, the icon has emitted a remarkable fragrance.

This

is painted on the wall above the outer gate of the Monastery. In 1822, a group of Turkish soldiers arrived at the Monastery and one of them, seeing the icon, shot at it, the bullet

making a hole in the Virgin’s right hand. As a result of this act, the soldier went mad and hanged himself from an olive tree in front of the Monastery. The rest of the Turks were

terrified by this divine retribution and left the Monastery immediately. Moreover, when the commander of the detachment was told of the act of the soldier, who was his nephew, he

ordered that he should be left unburied as a malefactor.

This

is painted on the wall above the outer gate of the Monastery. In 1822, a group of Turkish soldiers arrived at the Monastery and one of them, seeing the icon, shot at it, the bullet

making a hole in the Virgin’s right hand. As a result of this act, the soldier went mad and hanged himself from an olive tree in front of the Monastery. The rest of the Turks were

terrified by this divine retribution and left the Monastery immediately. Moreover, when the commander of the detachment was told of the act of the soldier, who was his nephew, he

ordered that he should be left unburied as a malefactor.

![]()

![]() This miracle-working icon dates from the 17th

century and hangs on the left hand shrine of the eastern column of the katholikon. According to the accounts of the elders of the Monastery, the first indication that this icon

bestowed especial grace was the following event: one day a young man entered the church and went to reverence the icon. Suddenly the face of the Blessed Virgin shone and some

unseen force hurled the young man to the ground. When he came to, he confessed with tears to the fathers that he had been living far from God and that he had been involved with

magic. The miraculous intervention of the Virgin resulted in the young man changing his way of life and becoming devout.

This miracle-working icon dates from the 17th

century and hangs on the left hand shrine of the eastern column of the katholikon. According to the accounts of the elders of the Monastery, the first indication that this icon

bestowed especial grace was the following event: one day a young man entered the church and went to reverence the icon. Suddenly the face of the Blessed Virgin shone and some

unseen force hurled the young man to the ground. When he came to, he confessed with tears to the fathers that he had been living far from God and that he had been involved with

magic. The miraculous intervention of the Virgin resulted in the young man changing his way of life and becoming devout.

This icon also has the property and special grace from God of healing the dreadful affliction of cancer. Large numbers of cancer-sufferers have been healed in recent times following a supplicatory canon chanted before the icon of Our Lady Pantanassa.

Sabbas, deacon-monk and sacristan (10th century).

Athanasius, Nicholas and Antonius, founders, from Adrianople (10th century), feast day: 17 December.

Sabbas, Archbishop of Serbia (1169-1235), feast day: 14 January.

Symeon, father of St Sabbas and King of Serbia (1200), feast day: 8 February.

Euthymius, Abbot, and his companions, 12 monk martyrs (1285), feast day: 4 January.

Cosmas, Protos, martyr (1285), feast day: 5 December. Gennadius, Abbot of the Monastery (14th century), feast day: 20 January.

Neophytus, ‘attendant’ (14th century), feast day: 20 January. Gennadius, manciple (14th century), feast day: 17 November. Agapius and Nicodemus, servants of the Blessed Gennadius (14th century).

Sabbas, ‘the fool for Christ’s sake’ (1280-1349).

Nicodemus, teacher of St Gregory Palamas (13th century), feast day: 11 July.

Gregory Palamas, Archbishop of Thessaloniki (1296-1359), feast day: 14 November.

Theophanes, Metropolitan of Peritheorion (14th century). Joasaph of Meteora (1394-1401), feast day: 20 April. Macarius Macres (1391-1431), feast day: 8 January. Maximus the Greek (1470-1556), feast day: 21 January. Macarius, martyr, disciple of St Niphon, Patriarch of Constantinople (1527), feast day: 14 September. Theophanes, martyr (1559), feast day: 8 June. Athanasius III of Constantinople (1656), feast day: 2 May. Agapios from the Skete of Kolitsou and his four blessed companions, feast day: 1 March. Dionysios, martyr (1822).

Evdokimos ‘the Newly-Found’ (1840), feast day: 5 October, loakeim Papoulakis (1786-1867), feast day: 2 March.

All the saints of Vatopaidi are commemorated by a festal vigil on 10 July.

kathisma: Accommodation for monks seeking greater solitude separate from the monastery buildings.

kelli: ‘Cell’. Dependency of a monastery ceded for their accommodation to not more than six monks.

kyriakon: Church serving a number of (often scattered) monastic dwellings.

lavra: A monastic complex, predating the coenobium, consisting of separate accommodation or cells grouped close to each other.

metochi: A dependency of a monastery, whether a cell or an estate, usually with its own church or chapel.

phiale: Roofed openair basin for holy water, serving liturgical purposes.

piastre:Turkish unit of currency equivalent to 1/100 of a Turkish lira.

poungeion: Literally, a money bag. The amount differed according to the size of the bag, but it was generally a very large sum.

Protos: ‘The First’-the monk who presides over the executive council of four appointed from among the members of the Synaxis (q.v.) to administer the affairs of the Community of Athos.

sigillium: Document issued by the Ecumenical Patriarchate regulating matters of ecclesiastical discipline and administration.

Synaxis: Council, with its seat in Karyes, consisting of a representative from each of the 20 monasteries; the authority through which the Athonite Community exercises its autonomy.

synodikon: Reception room in a monastery used for entertaining guests and other gatherings.

synthronon: Seats, usually of stone, around the sanctuary apse of a church, behind the altar, used by the bishop and his clergy in early Christian worship.

typikon: A kind of ‘charter’ of a monastery regulating matters of order and worship.

A PILGRIM’S GUIDE TO THE GREAT AND HOLY MONASTERY OF VATOPAIDI WAS PUBLISHED BY THE GREAT AND HOLY MONASTERY OF VATOPAIDI IN AUGUST 1993

TRANSLATION INTO ENGLISH BY GEOFFRY COX AND JOHN SOLMAN PRINTED BY A. MATSOUKIS S.A. EDITING FOR THE PRESS BY CHRYSOULA KAPIOLDASI-SOTIROPOULOU

The photographs on the cover and nos 1, 3, 8-13, 16-19, 21, 22, 25-31, 33, were taken by Mr Andreas Smaragdis, and nos 4-6, 14, 15, 20, 23, 24, 32, by Mr Charalambos lakovou.

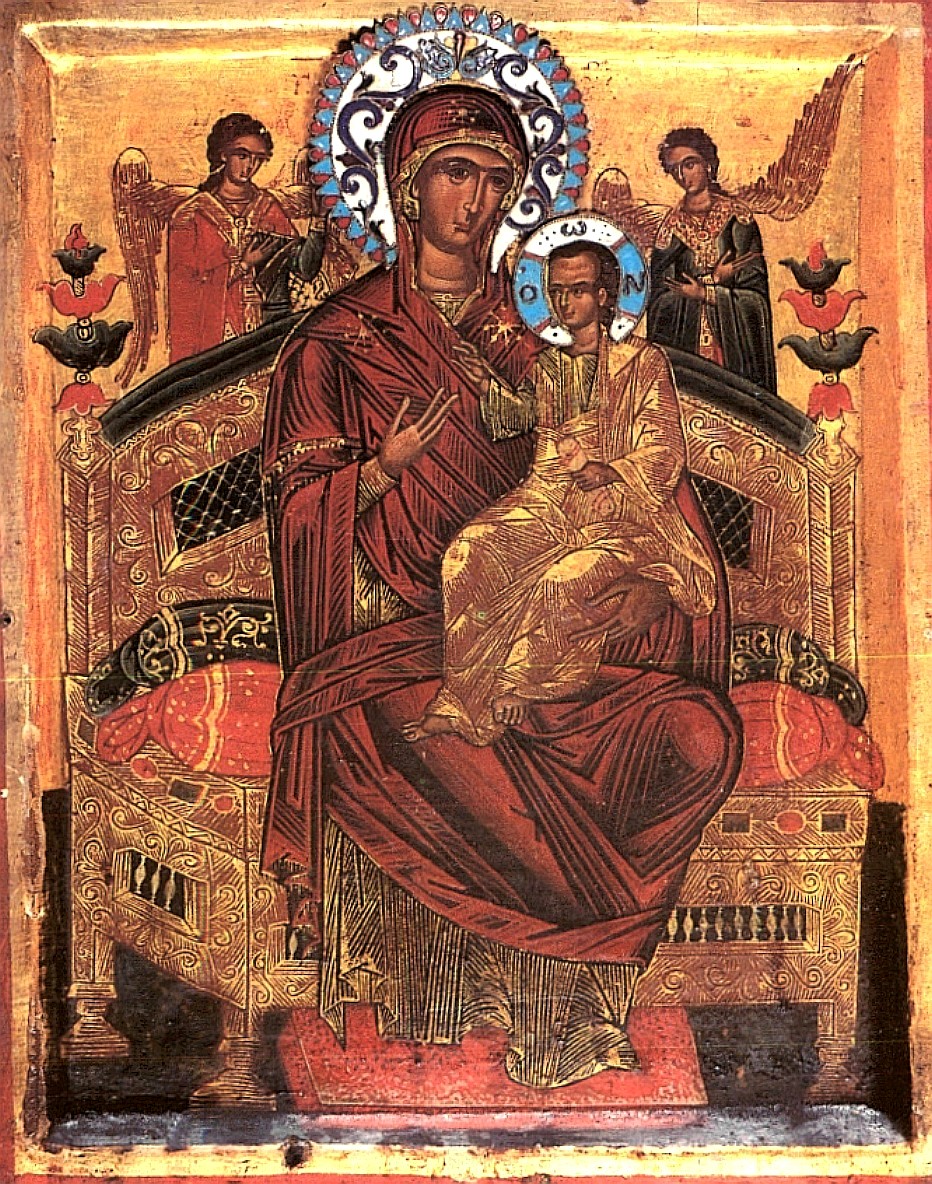

Our Lady Hope of the Despairing. From the diptych of the so-called ‘ninia’. Late 12th century (front cover).

Schematic representation of the Monastery on the handle of a liturgical fan (back cover).

Source: http://vatopaidi.wordpress.com